Intro

When did every one become a nutrition expert?

Wishful thinking, illogical fallacies, and misconceptions passed along in the health and fitness community have seemingly deterred folks from finding the practicality and truth in nutrition.

Todd Weber PhD, MS, RD and Mike Polis MS, RD, LD join forces to tackle some common nutrition misconceptions and deliver cogent, viable, scientifically sound nutrition information.

Myth #1 – “I need to limit my intake of fruits and vegetables because they contain too much sugar”

Of all the nutrition claims out there, this one ranks as one of the craziest.

In my experience this misconception is often the result of the following situation: a personal trainer or nutritionist asks a client to recall the foods they ate in the past few days.

The client recalls his/her diet and the diet the client recites is nearly perfect: appropriate amounts of fruits, vegetables, lean meats, whole grains, and low-fat dairy.

The nutritionist/personal trainer usually knows where the trouble spots in a diet are and realizes the client needs to cut calories to reach his/her weight loss goals but in this situation cannot figure out where the client needs to cut calories to reach these goals.

After analyzing the diet the trainer isn’t going to suggest cutting back on sources of lean protein such as fish, chicken, low-fat dairy or healthy fats/vitamins such as avocados, or salads.

Instead, fruits and vegetables, especially starchy vegetables, or those perceived as starchy vegetables (carrots) are going to be “called out” as the culprits and eliminated from the diet.

The client will be told that he/she cannot lose weight because they are eating too much sugar coming from fruits and vegetables. As a nation, we have become fixated on sugar when really we should be concerned with calories, not sugar.

Do you know how many calories are in this 2 pound bag of baby carrots?

1) 225 calories

2) 350 calories

3) 563 calories

4) 851 calories

If you ate this entire 2 pound bag of baby carrots you would still only be consuming 350 calories (or the equivalent of eating less than 2/3 of a Big Mac). Another example of how few calories carrots (a supposedly high sugar vegetable) contain, one baby Twix bar (50 calories) contains the same number of calories as 14 baby carrots.

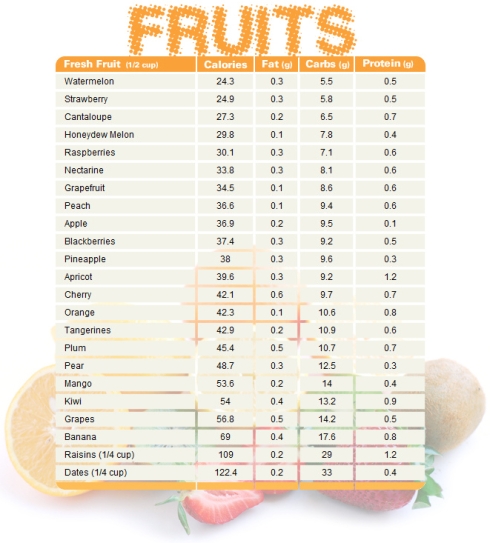

I think that most of us would agree that, on average, fruits contain slightly more sugar than vegetables. Yet, if we compare the number of calories in a baby Twix bar versus ½ cup of commonly eaten fruits (Table 1) you will see that in 17/21 cases you would actually save calories by eating ½ cup fruit in comparison to a baby Twix bar!

When someone tells you to stop eating fruits and vegetables because there is too much sugar in them, tell them to

1) shut up and that

2) their math doesn’t make any sense.

I would NEVER cut fruits and vegetables out of your diet. Instead, focus on 1) expending more energy through daily activity and/or 2) reducing the serving sizes/portions of every part of your diet (lean meats, whole grains, etc), not just fruits and vegetables.

Myth #2: “Dairy products promote inflammation and chronic disease.”

When you hear the term “inflammation” a negative connotation likely comes to your mind. We have been conditioned to dislike inflammation and rightfully so. Chronic low grade inflammation has been associated with the development of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and some forms of cancer (1). For the good of our health, we are told to avoid (or suppress) inflammation at all costs.

So does this mean we should avoid dairy to limit inflammation?

If you Google search “dairy products and inflammation” your suspicions that dairy produces considerable amounts of inflammation will be confirmed.

The first four search results indicate that your friend or trainer (or the internet) who told you dairy wasn’t good for you was right. However, the scientific community, by enlarge, has come to the opposite conclusion!

Dairy consumption actually reduces inflammation! In a recent cross-sectional study individuals consuming >2 servings/dairy/day had concentrations of molecules associated with inflammation in their blood between 10 and 30% lower than individuals consuming <1 serving/day (2). Now to be fair, there are studies for and against dairy’s role in promoting inflammation; however the majority of systematic reviews of this issue demonstrates that dairy actually improves your inflammatory profile by lowering inflammation, not raising it (1,3,4).

The reasons why dairy may actually improve your inflammatory profile are complex and poorly understood but may be due to the calcium, magnesium, vitamin D or other yet undefined proteins found in dairy products.

So the bottom line is, if you currently eat dairy, keep eating it. If you don’t like dairy or can’t eat dairy don’t worry, there are other foods you can eat to obtain the nutrients you would otherwise consume by eating dairy. Dairy and inflammation? Keep worrying about your real problems and don’t waste your energy on those that are pretend.

Myth #3: “Processed food is junk food and should not be eaten.”

A recent review article on processed food posed the question, “Is ‘Processed’ a Four-Letter Word?…” (5).

This question is indicative of the stigma that processed foods conjure up when discussed by many health conscious Americans. In response to the term “processed” food, some health conscious Americans are prone to saying things such as:

“I would never allow my children to eat processed foods.”

“Processed foods contain dyes, additives, adulterants, and chemicals harmful to you or your children.”

“You should only be eating whole, natural foods.”

Yes, I agree that we should all be eating whole, natural foods but not all of us have the taste, time, culinary skills, or budget to prepare and eat only whole, natural foods. Processed food, like virtually every nutrition topic, is not black or white, 1 or 0, yes or no. There is a certain amount of gray area in the discussion of nearly every “processed” food’s nutritional content.

There is a difference between processed food and what you would call “junk food” and not all processed food should be considered junk food. Yes, Doritos, Cheetos, soft drinks, cakes, and cookies are junk food as they deliver essentially ZERO nutritional value but what about cereal, pasta, bread, fortified products, canned beans, and canned fruits and vegetables? These foods have been considerably processed and are far from their native, natural state, yet in many cases, are vital contributors to the nutritional quality of the typical American’s diet.

When we dissect an American’s diet between the years 2003 and 2008 on the basis of the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (6), we see that processed foods contributed

55% of dietary fiber

48% of calcium

43% of potassium

34% of vitamin D

64% of iron

65% of folate

46% of vitamin B-12

These nutrients are extremely important to our health and processed foods contributed to greater than 50% of several of them. On the other hand, processed foods also contributed to

57% of total calories

52% of saturated fat

75% of added sugars

57% of sodium

Whether a food comes in a can, is frozen in a bag, is far removed from its original state (cereal), is dried, fortified, or enriched, processed foods contribute a considerable amount of nutrition to the American diet. Without food processing and food fortification many Americans would not meet their dietary goals. Processed food doesn’t necessarily mean junk food. Processed food that is nutrient dense (tightly packed with nutrients) is NOT junk food. Junk food is food that is calorie dense (tightly packed with calories) and not nutrients.

Before you stigmatize someone for telling you they recently ate a “processed” food, consider whether that food was nutrient dense or calorie dense.

Is processed food a four letter word?

I don’t think so.

Myth #4: “To lose weight, you should eat 5-6 small meals a day.”

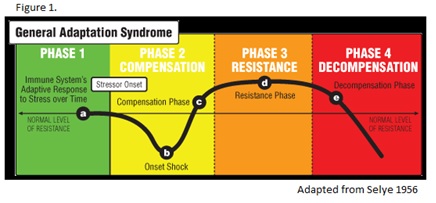

If you have ever stepped foot in a gym I think you have probably heard this line before, “The best way to boost your metabolism and lose weight is to eat 5-6 small meals/day”. The theory behind this nugget of wisdom is that your metabolism increases each time you consume a meal and decreases in between meals.

To keep your metabolism “firing” it is best to spread your meals out throughout the day to take advantage of this increase in metabolism with meal consumption (known as the thermic effect of food).

But is this story really true?

Let’s dive into this issue by first examining the driver of weight gain or weight loss, energy balance.

Energy Balance

In simplest terms, think of nutrition as a system with an input and an output sector.

Input includes the foods and beverages we consume (calories).

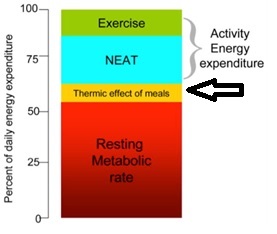

Output includes our resting energy expenditure (REE), the thermic effect of food (TEF), structured exercise energy expenditure, and involuntary movement.

- REE refers to the rate at which the body expends energy while at rest to operate basic life functions — such as breathing, sweating, filtering blood, and heart rate.

- TEF is the energy used to digest, absorb, and distribute the nutrients in the food and drink you consume.

- Structured exercise energy expenditure is just that. The amount of calories we burn during (and after) exercise. This is typically referred to as active energy expenditure (AEE).

- Involuntary movements include energy expended through non-planned exercise activities such as fidgeting at our desks, tapping our foot, pacing, or walking to your vehicle after work. These movements are also referred to as NEAT (non-exercise activity thermogenesis).

Exercise and REE: Burn baby, burn

Eating frequently in an effort to crank your metabolism into high gear stems from archaic epidemiological research and non-evidenced based claims perpetrated by fitness enthusiasts.

As calories are restricted, the TEF is reduced and if we are trying to lose weight, eating smaller, more frequent meals may actually do more harm than good.

In essence, the fewer calories (energy) we take in combined with a high meal frequency, may lower the overall response of the TEF (7).

To make matters worse, evidence has indicated that as we decrease the number of calories we consume, we also typically become less active. Not necessarily less active with conscious exercise, but perhaps less active expending energy via NEAT and involuntary bouts of movement (8).

Combine this with a decrease in REE (a natural byproduct of a decreased calorie intake and weight loss) and we are drastically decreasing our overall caloric burn.

Yet another reason not to get on the “small frequent meal bandwagon” is that research has suggested the effect of meal frequency on metabolism does not lead to a greater fat oxidation (9).

Please note: fat oxidation is required for weight loss.

Finally, it should also be noted that the TEF constitutes a measly ~10% of total daily energy expenditure while BMR and exercise (including NEAT) make up the bulk (90%) of energy expenditure (see picture below).

So, what should I be doing?

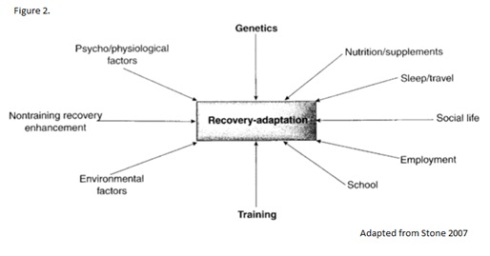

Shifting one’s focus to:

1. controlling calories and macronutrients based on your estimated needs while

2. using exercise to increase energy expenditure,

3. acquiring (lean body mass) development via resistance training, and

4. reaping the benefits of the” after burn” effect from high intensity training and thereby creating the real “thermic effect.”

In summary, there is no conclusive evidence that an increase in meal frequency correlates with a higher metabolic rate and/or reduction in body fat – given total calorie intake is controlled for (11, 12), which ties in with evidence which suggests no correlation between a higher meal frequency and fat oxidation (9).

The TEF is completely independent of REE, the energy burned at rest by the human body. Lean body mass (LBM) and activity level, both of which are independent of TEF, are the primary drivers of your metabolic capacity.

If the TEF resulted in a higher “metabolic rate,” an increase in meal frequency would likely increase LBM and BMR.

To date, there is no data supporting this hypothesis.

As I mentioned earlier, but cannot stress enough, a decrease in metabolic rate is the byproduct of restricted calories and perhaps a decline in NEAT vs. a lower meal frequency.

So, what do I know?

Eating 5-6 small meals may actually:

1) Decrease the thermic effect of food (TEF).

2) Do nothing for weight loss or increased fat oxidation.

Practicality of meal structure

Select a meal pattern that is most appropriate for your schedule and needs.

Listen to your hunger cues and become more in-tune with your body’s physiology by answering the following questions:

• Are you mistaking hunger for thirst?

• Are you low on dietary protein consumption? (Note that dietary protein promotes feelings of fullness and satiety, which can keep hunger levels at bay).

• How many meals/day feels right to me?

• Do I need to change the times I eat my meals to get through the day?

• Do I need to eat a larger breakfast or lunch to make it to supper?

Following an arbitrary “8 meals per day” protocol because your favorite professional bodybuilders and figure competitors do so is only opening the door for unwanted gastrointestinal distress and a decline in finding enjoyment in your food.

Select the meal pattern that is most appropriate for you schedule and your needs and call it the (insert your name here) plan.

Myth #5: “For building muscle, the more protein, the better.”

Dietary protein has long been associated with “muscle building” in the general fitness community. And there is certainly some truth to that. However, context is also important.

Let’s take a look.

Protein requirements are individualized based on your goals, height, weight, age, gender, body composition, and activity level.

More protein in the diet does not necessarily translate to more muscle on Jane Doe’s frame. There is a dose dependent response with protein, and possibly an anabolic cap to just how much protein you can effectively absorb and digest.

Strength athletes and folks focused on building muscle may benefit from a higher protein intake but how much is too much and how much is just right?

The current Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) for protein for folks at a healthy body weight (BMI<25) is 0.8g-1.0/kg body weight; however, this estimate does not take into account metabolic demands and stressors related to training.

For the strength athlete or physically active individual, 1.4-2.0g/kg of bodyweight is a safe, effective baseline recommendation for protein intake.

In fact, this recommendation may actually enhance training adaptations according to the International Society of Sports Nutrition (13).

Why do athletes benefit from an elevated protein intake vs. the current RDA recommendation?

Protein synthesis is increased, leucine oxidation is decreased, and nitrogen balance is preserved with an increased protein intake (14). This phenomenon creates an atmosphere conducive to muscular growth and hypertrophy.

Protein intake is a highly individualized component of nutrition that requires consideration of training variables, overall calorie intake, energy expenditure, current LBM, and overall goals.

The ISSN recommendation of 1.4-2.0g/kg serves as a great baseline for protein intake and the athlete or active individual.

Higher protein intakes may be warranted for resistance-trained, lean bodybuilders with a lower body starting point, especially when in caloric restriction, in efforts to preserve fat free mass (FFM) (14).

For example, a trained individual deep into contest prep for a bodybuilding or figure competition on a calorie restricted diet may benefit from protein needs beyond the 1.4-2.0g/kg recommendation.

A competitive powerlifter with low body fat (more metabolically active tissue) who’s training consists of high frequency with periodized mesocycles of volume and intensity blocks may have more of a metabolic demand for higher protein intakes as well – given total caloric intake is accounted for.

Furthermore, trained natural athletes typically add lean body mass at a relatively slow pace.

In my experiences, if a natural athlete can add 1-3 lbs. of actual lean body mass a year — that is remarkable.

Marketing ads claim you can add 15-20 lbs of muscle a year by taking this natural XYZ supplement or by following this XYZ diet.

This simply is not feasible for a trained, natural athlete.

Adding lean body mass to one’s frame is a tedious process that takes time, patience, and precision in both nutrition and training.

Two pounds of lean flank steak. Imagine two pounds of lean body mass accumulation on your frame. That is quite a bit of fat free tissue!

Again, protein intake needs to be individualized within the parameters of one’s diet and goals.

One size does not fit all.

Myth 6: “Creatine is a harmful, unnatural substance.”

Let me preface this section of the article by stating that creatine is not a steroid.

Just the other day, I heard overheard a grown man at the gym stating creatine was a steroid.

False.

Creatine is a molecule used in the body’s innate energy systems that produces adenosine tri-phosphate (ATP).

Creatine is not hormonal. Creatine is a safe supplement with over twenty years of research (15).

In fact, creatine is found naturally in small quantities in most of our meat products such as chicken, turkey, fish, and red meat.

When an individual supplements with creatine, the body stores the creatine as phosphocreatine to later be released as energy from the cell during bouts of high-intensity exercise such as sprinting or completing a 3 repetition max (3RM) on the barbell squat.

Most literature reviews and meta-analysis studies report positive effects when creatine is supplemented during periods of high-intensity exercise (17). When the effects of creatine supplementation on performance and training adaptations were reviewed, some research reports an average increase in sprint performance upwards of 5% and increases in both muscular strength and repetitions to failure by 5-15% (17).

However, if you are a long distance runner (any distance greater than 1 mile), creatine will not improve your performance because your body is relying on a different set of energy systems for this duration of exercise.

There are several forms of creatine on the market, but creatine monohydrate is the:

a) most commonly used in studies

b) most heavily researched

c) most cost-effective

If I want to supplement with creatine, the manufacturer recommends I “load”. Is loading really necessary?

Creatine loading refers to “cycling” creatine with a loading phase, a maintenance phase, and an “off week.”

For the loading phase, an individual would take 20g creatine for 5-7 days. This is “necessary” for creatine reserves to accumulate/top off in our muscle cells.

Then for the following 4 weeks, 5g each day is recommended. After 4 weeks of taking 5g per day, take a week off from supplementing creatine.

This is an example of a loading phase.

In my opinion, the more common (and the more cost-effective method of taking creatine) is simply supplementing 3-5g creatine daily. Your rate of muscle saturation with creatine will be much less vs. loading initially, but muscle creatine saturation will eventually be equivocal.

Bottom line: loading creatine is not necessary and the benefits are doing so are trivial compared to traditionally taking 3-5g creatine daily.

Taking creatine is safe and, in power based sports of short duration, is effective in potentially increasing performance by up to 15%.

If you are looking for a little boost in your performance and don’t mind shelling out a couple of bucks, creatine may be your supplement.

References:

1. Da Silva MS, Rudkowska I. Dairy nutrients and their effect on inflammatory profile in molecular studies. Molecular nutrition & food research. Jul 2015;59(7):1249-1263.

2. Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos CH, Zampelas AD, Chrysohoou CA, Stefanadis CI. Dairy products consumption is associated with decreased levels of inflammatory markers related to cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy adults: the ATTICA study. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. Aug 2010;29(4):357-364.

3. Labonte ME, Couture P, Richard C, Desroches S, Lamarche B. Impact of dairy products on biomarkers of inflammation: a systematic review of randomized controlled nutritional intervention studies in overweight and obese adults. The American journal of clinical nutrition. Apr 2013;97(4):706-717.

4. Markey O, Vasilopoulou D, Givens DI, Lovegrove JA. Dairy and cardiovascular health: Friend or foe? Nutrition bulletin / BNF. Jun 2014;39(2):161-171.

5. Dwyer JT, Fulgoni VL, 3rd, Clemens RA, Schmidt DB, Freedman MR. Is “processed” a four-letter word? The role of processed foods in achieving dietary guidelines and nutrient recommendations. Advances in nutrition. Jul 2012;3(4):536-548.

6. Weaver CM, Dwyer J, Fulgoni VL, 3rd, et al. Processed foods: contributions to nutrition. The American journal of clinical nutrition. Jun 2014;99(6):1525-1542.

7. Miles CW, Wong NP, Rumpler WV, Conway J: Effect of circadian variation in energy expenditure, within-subject variation and weight reduction on thermic effect of food. Eur J Clin Nutr 1993, 47:274-284.

8. Rosenbaum, M et al. Effects of experimental weight perturbation on skeletal muscle work efficiency in human subjects. Am J Physiology Regul Integ Comp Physiology.. 2003 Jul;285(1):R183-92. Epub 2003 Feb 27.

9. Marjet J. M. Munsters, Wim H. M. Saris. Effects of Meal Frequency on Metabolic Profiles and Substrate Partitioning in Lean Healthy Males. PLoS One. 2012; 7(6): e38632. Published online 2012 June 13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.003863.

10. McArdle, William D., Frank I. Katch, and Victor L. Katch. Exercise physiology: nutrition, energy, and human performance*. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2015.

11. Taylor MA, Garrow JS. Compared with nibbling, neither gorging nor a morning fast affect short-term energy balance in obese patients in a chamber calorimeter. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001 Apr;25(4):519-28.

12. Verboeket-van de Venne WP, Westerterp KR. Influence of the feeding frequency on nutrient utilization in man: consequences for energy metabolism. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1991 Mar;45(3):161-9.

13. Campbell B, et al International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: protein and exercise . J Int Soc Sports Nutr. (2007).

14. Wilson J, Wilson GJ Contemporary issues in protein requirements and consumption for resistance trained athletes . J Int Soc Sports Nutr. (2006).

15. Helms ER, Zinn C, Rowlands DS, Brown SR: A systematic review of dietary protein during caloric restriction in resistance trained lean athletes: a case for higher intakes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2013.

16. Groeneveld GJ, et al. Few adverse effects of long-term creatine supplementation in a placebo-controlled trial . Int J Sports Med. (2005).

17. Kreider RB. Effects of creatine supplementation on performance and training adaptations. Mol Cell Biochem. (2003) 244(1-2):89-94.